The Dangers of Leading With Your Head

A few weeks ago, a friend of mine whose son plays Division I baseball told me a story. She was watching her son’s game on television when a player (not her son) dove headfirst into second base on an attempted steal. The runner’s head smashed into the shortstop’s knee, whereupon the runner collapsed on the field. For many moments, the players, coaches, and umpires didn’t know if the runner was alive – he certainly wasn’t moving. After about five interminable minutes, the player regained consciousness and was helped from the field. He was later diagnosed (luckily, as it happens) with only a concussion.

My friend told me this story as a prelude to a question that I have been asking in various forms for years: Why do players slide headfirst? Why is this even allowed?

Now, I am sure there are old-timers out there who will tell me that banning headfirst slides would be un-American; a violation of individual rights; a further wimpifying of our culture; that it would be pillow-parenting run amok. Okay, fair enough. Here in America you are entitled to your opinion, as am I.

It seems like I write about this issue every year. It turns out I have only done so in 2015, 2016, 2017, 2019, and now 2022. And the reason I keep writing about it is because it is still an incomprehensible practice.

The issue came top of mind a few weeks back when I watched one of my favorite young players – Ke’Bryan Hayes – do something so monumentally stupid that I could not believe my eyes. And it made me question what his father (a former big leaguer) taught him, and what type of coaching he is receiving in the Pirates organization. Here was the situation:

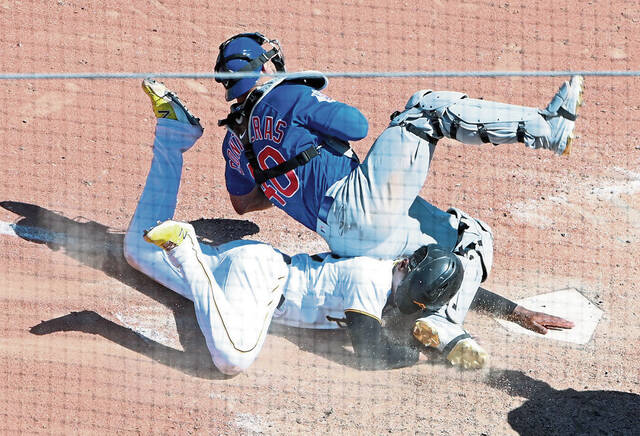

Hayes was on second as the Manfred-Man to start the bottom of the 10th inning. With one out, Michael Chavis hit a short looper over first. Hayes never stopped running. Rafael Ortega scooped the ball up on one hop, turned, and fired a strike to home plate. Waiting to receive Ortega’s throw was well-known (illegal?) plate blocker Willson Contreras, all 225 pounds of him. So what did Hayes, three inches shorter and at least 20 pound lighter – not accounting for the mass of equipment Contreras was wearing – do? He dove headfirst into home plate, where he met the Cubs’ catcher, and his heavy plastic shin guards, and his oversized backside. Hayes scored the winning run, and then lay in the dirt for nearly a minute. The Pirates’ play-by-play guy stated: “I have never seen a celebration muted like this.”

Hayes was helped to his feet and off the field, and then missed then next two games with a sore shoulder. He was lucky it wasn’t considerably worse; but since he has been back in the lineup over the last nine games, he is 6-for-35, with no extra base hits. Because correlation does not prove causation, you can draw your own conclusions.

Why did Hayes dive into home rather than sliding feet first? Why not utilize a classic hook slide moving his entire body as far from Contreras, who was catching a ball thrown from right field, and thus could not get a specific bead on the runner? Or, for all you throwbacks out there, how about him knocking Contreras’ block off – Pete Rose style – in the hope of dislodging the ball from his mitt? I think a replay review would have shown that Contreras did not provide Hayes with a path to the plate prior to his receiving the throw. Any of those options would have been better than putting his fingers, hands, wrists, neck, head, and shoulders at risk. Why didn’t the Pirates coaching staff alert the players in their scouting report that Contreras likes to block the plate? Why didn’t the Pirates player development staff coach their players to be safe, not sorry, when trying to advance to the next base? Why?

Sure, we all love watching Javy Báez with a swim slide into second base avoiding the tag of an unsuspecting middle infielder. But, at what cost? In 2019, Báez dove into second base, fractured his thumb, and missed the month of September. Some lessons are never learned.

Since the Hayes incident, I have seen a handful of additional players dive into home plate, all avoiding serious injury. But that is just dumb luck. Baseball is a dangerous game on its own. Don’t believe me, ask:

- Mookie Betts (ribs, from an outfield collision)

- Jacob deGrom (shoulder)

- Manny Machado (ankle, running to first)

- Max Scherzer (oblique)

- Salvador Perez (thumb, due to a swing)

- Ozzie Albies (fractured foot from a foul ball)

- Walker Buhler (flexor strain and bone spur)

- Stephen Strasburg (ribs)

- Chris Sale (ribs)

- Bryce Harper (thumb, due to a HBP)

- Anthony Rendon (wrist, due to an errant swing)

- Jazz Chisolm, Jr. (back strain)

- Jack Flaherty (shoulder)

- Tyler O’Neill (hamstring)

- Hunter Renfroe (calf)

This list could go on and on. The point is that there is enough that can go wrong on a baseball field that players don’t need to take it upon themselves to up the ante. Sliding headfirst has shown, time and again, to be a fool’s bargain; and as I wrote in 2016, extremely costly. MLB teams need to get smart about this. But so, too, do college teams. And high schools. Yes, it is legal there as well.

When and where will the madness stop? When an aspiring physicist or politician or doctor playing baseball for an Ivy League institution dies on the field because his neck and head couldn’t endure the impact with another kid’s knee? Or will it require a $30M/year superstar becoming paralyzed on a major league diamond in front of 40,000 fans and on national television because he believed that leading with his head offered him the best chance to score a run in the fifth inning of a 7-2 ballgame?

MLB has shown a willingness to change its rules when big-name players get injured on a big stage (see, the Chase Utley Rule; see, the Buster Posey Rule). Why wait until we have to name this new rule? Or, if we must, let’s call it the Hayes Rule, named for a legacy player who narrowly avoided disaster and forced baseball to do the same.

PLAY BALL!!