When Safe is Out

I am an attorney. As such, my bookcases are stocked with legal tomes, filled with confusing text, obscure events, and various and sundry arcana. After practicing for nearly twenty years, I rarely reach for any of these dusty books, as it is often difficult to discern the meaning of anything written in them.

Among the those littering my office is the Official Baseball Rules. This softback, covering 240 pages, is also filled with ambiguous regulations, bizarre concepts, and wacky examples. The amazing thing is, armed with this book, not one of us could stump an MLB umpire. Wake an umpire in the middle of the night, and he could opine on the specifics of Rule 6.01(g) (Interference With Squeeze Play or Steal of Home) before he rubs the crust out of his eyes.

But umpires are limited by what they find in those 240 pages. So, from time to time, it is incumbent upon the MLB Rules Committee to enact some new rules to deal with the evolution of the game. This became painfully obvious late last week.

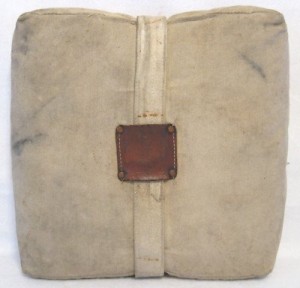

Years ago (before any of us were watching or playing baseball), bases were soft and billowy, filled with sand or sawdust, affixed to the ground via a leather strap attached to a wooden spike.

Today, bases are made of hard rubber and have a metal attachment that connects to a steel tube anchored by concrete in the ground. Suffice it to say, today’s bases are considerably less hospitable to the players trying to reach them.

In the hundred plus years or so between the advent of baseball and the current incarnation, players – on average – have gotten about 5 inches taller (average height in 2010 was nearly 6’2” vs. 5’9” in the 1870s) and about 23 pounds heavier (190 now vs. 167 then). Now, I don’t want to get all Sports Science here, and I certainly don’t want to start doing math or coefficients, but I think we can all agree that players today are faster than they were in the 19th century, and because they are taller and heavier, they run with more force than players from the Rutherford B. Hayes-James Garfield-Chester Arthur-Grover Cleveland era. And yet, today’s ballplayers are required to interact with a base that has considerably less (read: no) give. This is where many problems arise.

I have written (extensively) about the dangers of sliding head first into bases (as well as home plate), but neither José Lobatón nor the Washington Nationals care about injuries right now. They are more concerned with basic physics. And here’s why:

With two outs and the Cubs leading 9-8 in the bottom of the 8th inning of Game 5 of the NLDS, the Nats had one run in and two runners on when Willson Contreras threw a back-pick to Anthony Rizzo at first base, hoping to catch Lobatón napping. He wasn’t, and got back safely. Or so we thought.

Upon further review, when all 73 inches and 205 pounds of Lobatón slid feet first and impacted the 15×15 inch rubber square that is essentially bolted to the earth, the result was not flawless. Lobatón’s right leg hit the bag and then, ever-so-slightly, lost contact with the base. When bodies of considerable mass make contact with immovable objects, these types of things tend to happen. Rizzo adroitly held his tag, and the replay guys in New York were able to find a fraction of an inch of daylight between the foot and the base. Rally over…inning over…season essentially over.

This is not an issue of fair vs. not fair. Those are the rules, have been since time immemorial, and Lobatón was correctly called out. But when something like this happens, in a game of this magnitude, it just means we need to change the rules. As players get bigger and bigger and faster and faster (either naturally or otherwise), we need to make sure that the game is in a position to make accommodations, and we need to allow for umpires to make reasonable calls in relation thereto.

Because disconnecting with the bag for a fraction of a second and being called out certainly is not in the spirit of the game, Dave Cameron of Fangraphs came up with a solution last year that he reposted again after Thursday night’s debacle in Washington. In short, he wants a vertical “safe space” above the bag to account for these types of plays. It is an interesting concept, and I encourage you to give it a read.

I would augment, supplement, or replace Dave’s idea with the following (taking out the concept of verticality or any other plane):

If a base runner, sliding either head first or feet first, reaches the base prior to the application of the fielder’s tag, and the base runner loses contact with the base, in the umpire’s judgment, for reasons other than his own volition (i.e., only due to the impact of his body to the base), and in the umpire’s judgment the base runner had no intent to advance to the next base, provided the loss of contact is for a de minimis period of time, the base runner shall be ruled safe. The foregoing shall not be applicable to instances wherein the base runner slides past the base in question, regardless of the period of time he loses contact with the base. In such event, provided the tag is applied when the base runner is off the base, he shall be called out.

My version of the rule incorporates Dave’s vertical concept but allows for a player to go off to the side as well. I can imagine, without the benefit of a direct overhead camera, replay officials debating whether or not the impact caused the runner to bounce to the side of the base, in which event Dave would have him called out, or remained atop the base, resulting in ultimate safety. I guess I am just more liberal with my body movement allowance.

Take Dave’s idea, take my idea, or come up with another. But, sometime before the first pitch is thrown for the 2018 season, the MLB Rules Committee needs to fix this glaring omission, and get us back to what the rules intended, not what 4K Ultra HD digital technology discovered.

PLAY BALL!!