It’s Better to Be Lucky Than Good (or Smart)

The Dodgers and the Astros are two of the most analytically-driven organizations operating in baseball today. Andrew Friedman has a background in finance, and ran the low-budget Rays for years on a diet of limited dollars and copious spreadsheets. Jeff Luhnow came to the Astros (from the Cardinals) in 2011, armed with degrees in Economics and Engineering, and revamped the Astros’ front-office, installing a lose-to-win strategy (read: “tanking”), which paid off handsomely Wednesday night.

We, as fans, are not privy to the scores of data that are provided to the manager, coaches, and players before each series, ahead of each game, during each inning. So we are often left scratching our heads at decisions that look, to us, irrational. But to the managers, coaches, and players, they are all part of a master plan. We may not love this form of baseball; we may prefer decision-making from the good ol’ gut or based on something imperceptible to us, but glaring to someone who has spent a lifetime sitting on the top step of a dugout. Welcome to baseball in 2017.

For executives like Friedman and Luhnow, it is about having the world’s best inputs, the most rigorous analysis, and then trusting the #process to produce the most advantageous results. These types of leaders strive for outcomes derived from a thoughtful plan, which is predicated on the aforementioned input and analysis. Outliers are unimportant; what matters most are the aggregate fruit plucked from a well-planted decision tree.

However, even with all of the statistical back-up, the iPad on the bench, and laminated cards in the players’ back pockets, we witnessed a handful of, um, strategies, during the World Series that defy explanation. These were decisions that did not seem to flow from a thoughtful process or with a strong statistical advantage. After a thrilling World Series, seven games filled with tension, lead changes, and many, many homeruns, we won’t talk about these moments as they somehow ended in the team’s favor. Yet if these decisions had produced a different result, we may be discussing them for years to come. I guess sometimes it is better to be lucky than good (or smart).

Because Buster Olney, Joe Sheehan, Tom Verducci, Bob Nightengale, and Jerry Crasnick don’t have time to write about these; and before Jayson Stark finds the novelty in each one; and before Ben Lindbergh and Michael Baumann and Jeff Sullivan break them down to their most granular level; and before Joe Posnanski writes something pithy about them, allow me to address some of the 2017 World Series’s most head-scratching moments:

GAME 5

7th Inning: With the score tied at seven , Justin Turner led off with a double. Kiké Hernández hit only .159 against right-handed pitching this season, so asking him to bunt may have seemed like the correct call. But for a guy with nearly 1,000 career at bats, Hernández has a total of 2 sacrifice bunts. And it showed. Kiké bunted right to Brad Peacock who wheeled and threw out Turner at third. One out, runner on first. When Cody Bellinger tripled three pitches later, Hernández scored, and Kiké’s bunt and Turner’s out did not matter. But all of that begs the larger question: In a slugfest wherein 14 runs had been scored in the first six innings, did Dave Roberts honestly believe that one run over the next three would win the game?

9th Inning: This one doesn’t fall on the manager, per sé, but coaching may have played a role. After Yasiel Puig’s one-out, one-handed two-run homer in the 9th inning to cut the Astros’ lead to 12-11, Austin Barnes stretched a long single into a way-too-close-for-comfort double. Being aggressive is great, being reckless is not. A slightly better throw leaves the Dodgers with the bases empty, chasing a run, down to their last out. Chris Taylor singled home Barnes, tying the game, and now Barnes looks daring, not careless.

GAME 6

5th Inning: Rich Hill threw four innings in Game 2. After the epic Game 5 in which the Dodgers used seven pitchers throwing a total of 195 pitches, the conventional wisdom held that Hill needed to go deep into Game 6. Dave Roberts eschewed convention and scoffed at wisdom. After getting himself into a second and third no-out jam, Hill struck out Josh Reddick and Justin Verlander. That turned the lineup over with two outs. Roberts elected to intentionally walk George Springer to face Alex Bregman. I guess this was a lesser-of-two-evils dilemma with first base open: at that point, Springer was 8-23 with four homers and two doubles; Bregman was 7-24 with two homers, a double, and a walk-off hit the game before. Heads you win, tails I lose. With Springer now on first and the bases now loaded, Roberts pulled Hill after 58 pitches (45 strikes). So much for going deep. And he replaced Hill with the gassed Brandon Morrow. The same Brandon Morrow who gave up four runs over six pitches in his last outing. What did Morrow do? He induced Bregman to ground out to end the inning. Great result, but I’m not too sure about the process.

6th Inning: With the Dodgers trailing 1-0 and the pitcher due to bat second in the bottom half of the inning, Roberts elected to make a double-switch in the top half. Going by the book, Roberts removed the player who had made the last out. In doing so, he replaced Logan Forsythe, who was hitting .313 in the series, with Chase Utley, who was 0 for his last 29. Huh? Of course, no harm was done as Utley got hit by a 2-2 breaking ball and eventually scored on Corey Seager’s sac fly. (Side note: Can someone please explain to me how Seager’s flyball didn’t land ten rows into the Pavilion?)

7th Inning: The sixth inning ended with the Dodgers leading 2-1. Verlander was due to bat second. He had thrown 93 pitches, so he probably had another 35 in him. Upon leaving the field, Hinch told Verlander he was done for the night. Justin donned his jacket and got a drink of water. My question is why not wait to see what the leadoff hitter does? If Reddick gets on base, Verlander could (attempt to) bunt him over; and if Reddick fails, then you simply pinch hit for Verlander. But at least give yourself the option. Of course Reddick walked, and instead of having Verlander bunt him to second (or, at worst, strike out with Reddick stuck at first), Evan Gattis pinch-hit and rolled into a force out. After a Springer single, Hinch was forced to use Derek Fisher as a pinch-runner. Kenta Maeda then retired Bregman and Jose Altuve; and now the Astros had one less pinch-hitter and one less pinch-runner available. Oh, and they now had to go to the leaky bullpen instead of getting a little more out their horse while trying to keep the game in check. Joc Pederson hit a homerun off Joe Musgrove in the bottom of the 7th, so that didn’t work out so well. But the Astros won the World Series, and Verlander was available (?) out of the pen in Game 7, so I guess all’s well that ends well.

8th Inning: Two on, two out in the bottom half, Dodgers lead 3-1 with a chance to break it open. A.J. Hinch replaced Luke Gregerson with Francisco Liriano to face Cody Bellinger. At that moment, Liriano had not pitched in nearly two weeks – his last appearance was in Game 5 of the ALCS. In Liriano’s career, he has fared just slightly better against lefties than righties, and in Bellinger’s rookie season, he has a higher batting average against lefties than righties. So, yes, this was an odd decision. And, of course, Liriano struck out Bellinger (his fourth K of the game; his sixth in his last ten plate appearances; and in the midst of what would be nine out of fourteen to end the World Series).

8th Inning: Dave Roberts went to the Kenley Jansen well early in Game 6. Sure, this was a must-win. Sure, Jansen had been the best closer in baseball the past few seasons. But Jansen had also thrown in four of the last five games, he had thrown 90 pitches in the World Series, he already had one loss and one blown save, and given up a garbage-time homerun. So Roberts asked Jansen to record six outs, and then be ready to do the same in Game 7. Had the Dodgers been protecting a one-run lead, an argument could be made for this move. But shouldn’t a 104-win team with bullpen strength at least try to get an out or two out of Cingrani, Fields, McCarthy, and/or Stripling? Jansen went on to get six outs using 19 pitches (18 strikes), forcing a Game 7, and made Roberts look like a genius.

GAME 7

7th Inning: Speaking of misusing Jansen, what is the thinking behind having him take the mound so early in Game 7, while trailing 5-0? I get that you want to keep the Astros at bay, but Alex Wood did that in the 8th and 9th, and ostensibly could have done so an inning earlier. Assume – for the sake of making the game more exciting – that the Dodgers mounted a rally and scored four, five, or imagine, six runs in the seventh and eighth innings. Who was Roberts going to use to close the game after burning Morrow and Jansen? This seems like a risk not worth taking in a deciding game. Alas, the Dodgers couldn’t muster any offense and the issue became moot. But what if…?

THE WORLD SERIES

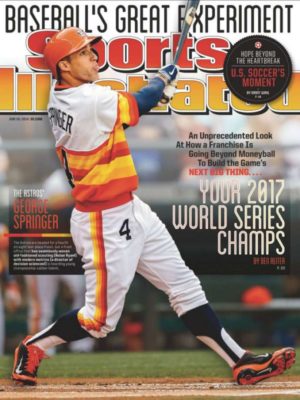

One would think – but I cannot opine with certainty – that big corporations have really smart people using really advanced data to make really difficult decisions every day. And I assume that publishers, in this subscription-troubled, online-centered, fragmented marketplace, are careful about what and how they market their wares. So it seems to me that making a bold prognostication – three years in advance – on the cover of one of your flagship magazines, is not in keeping with a conservative approach to investment returns. And yet, that is exactly what Time Inc. did with Sports Illustrated in June, 2014. Not only did SI get it right, they had the World Series MVP on the cover. Yup, sometimes it is better to be lucky than good.

PLAY BALL!!