KEEPING SCORE

KEEPING SCORE

We all know the old adage: The difference between a .250 hitter and a .300 hitter is a hit a week. One minor duck fart, quark, Baltimore Chop, Texas Leaguer, or frozen rope per week, and a guy is on his way to All-Star games and the possibility of mega-riches; one less and a guy is on his way to Triple-A – potentially out of baseball forever.

There is no corollary (in baseball adages, anyway) for pitchers; but the same concept applies. One less earned run per week, he goes from a 4.00 ERA to a 2.9 ERA. Again, one earned run less per week is the difference between the chance to make $1M per start, and being in the Minor Leagues, making about $85K per year.

Whether a hitter reaches base via hit or error, or whether a run is deemed earned or unearned, can have major financial implications.

And it’s not just hits and errors, but wins, losses, saves, and a whole litany of other potentially lucrative statistics. (Take a look at MLB Rule 10 for all kinds of nuggets.)

Simply put, a lot rides on one person’s assessment. Of course, with Sabermetrics and advanced stats like OPS and WRC and FIP and WHIP and BABIP, standards like AVG and ERA may be antiquated, but they are still oft-used and oft-relied upon – especially in contract negotiations.

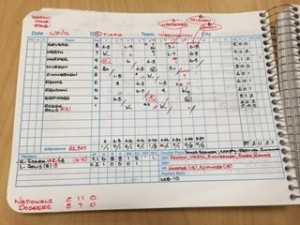

That means that the men and women who sit in the press box – more specifically, in the scorer’s box – and jot down dashes and dots, using multiple pens in multiple colors, creating chicken-scratch in small squares in a small pad of bound paper – have enormous power, whether they know it or want it.

We all know how to keep score. It started at our kid’s Little League game when you either drew the short straw or looked like someone who (a) knew the game or (b) paid attention or (c) didn’t have a ready excuse not to. You took “the book” with all those little diamonds, filled in the lineup, and did your best to keep up and keep track. No one really cared what you did as long as you got the score right and didn’t issue too many errors to the youngsters on the field (“come on, that was a hit . . .”). Easy enough.

But, for the many men and women who sit high above Major League stadiums every day, the stakes are considerably higher. And more people rely on that snap judgment than you can imagine. The scoreboard operator needs to signal to the fans; the television and radio announcers need to tell their respective viewers/listeners; hitters need to know if their batting average just went up or down; and pitchers need to know if what just happened on the field will affect their ERA. It all matters. And it all must be decided in a matter of seconds. How is it done?

Ed Munson, one of three official scorers for the Dodgers and Angels (he alternates), has been doing this for 37 years and scored over 3,500 games. He will tell you that he knows baseball, and goes with his gut. I was lucky enough to sit in the box with Ed one night not too long ago, and watch a master do his job. He made it look so easy. Trust me, as I kept my book next to his, it is not. And when Joc Pederson hit a shot up the middle into the shift, and Danny Espionza either couldn’t or wouldn’t get in front of it, Ed made the call immediately.

Up in the box, we had a short post-call debate. In the end, I begrudgingly agreed with his call (hit). And when Yasiel Puig grounded into an inning-ending double play on the next pitch – while it didn’t become moot (see AVG, above) – it became considerably less controversial. No one would have gained from that being ruled an error.

But, the official scorer cannot make decisions based on bias or potential value. He/she needs to make instantaneous calls based on angles, speed, skill, experience, and the rules of the game (a copy of which Ed keeps next to him every night – even though he knows the book cold).

Until about five years ago, it was not unheard of for a manager – or a player – to so vehemently disagree with a scorer’s decision that they would call up from the dugout to plead their case. While some viewed this as a Bush League move, others simply viewed it as too distracting to someone trying to do their job in real time.

In an effort to quell any such base instincts, the 2011 CBA gave the players a quiet, but important “win” and – in this process – essentially removed the term “official” from a scorer’s job description. Because now, rather than simply being subject to the whims of the official scorer, a player (or, more typically, his agent) has 72 hours to file an appeal. This involves an actual application, often accompanied by a video clip and an explanation as to why the call should be changed.

The appeal is sent to Joe Torre, MLB’s Chief Baseball Officer. Torre has full discretion, but – according to the rules – the call should only be changed if it was “clearly erroneous”. Torre customarily sends an email to the official scorer to get his/her interpretation of the play and their reasoning behind the call. He then has the option of consulting with other MLB officials to get their input; but when Torre renders his decision, it is final, it is “official”.

While you might think that longtime scorers feel usurped by Torre’s ultimate authority, the opposite is actually true. Mark Jacobson, who has been scoring Orioles games since 1992, told the Baseball Hall of Fame: “It is not a perfect system but … it takes it out of having to deal with the endless ‘did not, did so’ arguments in the press box because now you send it in, let Joe sort it out … and I can go home and not have to worry about whether I’m going to look at that play tomorrow”.

Stew Thornley, who scores for the Minnesota Twins, likes the new process because it is better than confrontations with players or team officials over a contested call.

Scorers have up to twenty-four hours to change any of their calls. Some, like Munson, record all of their games and go back and review any controversial play to make sure they got it “right” (or, at least, that their call was justifiable). But most scorers take their ego out of it – they don’t really care if their call is overturned by Torre, as long as there is sound reasoning. While that may seem counter-intuitive, it really isn’t. Think about the person who is willing to sit still for 3+ hours and watch every single pitch and record the outcome of every such pitch in a little notebook, with but one goal in mind: making sure that the plays on the field are judged correctly.

They aren’t doing it for the money: They get $170/game (some teams provide food, others don’t; they all provide parking).

They aren’t doing it for the accolades: Michael Duca, who scores for the Giants, told the SF Gate back in 2012: “If you’re doing the job right, you irritate all 50 players in both dugouts”.

They aren’t doing it for the fame: Ask any – even avid – baseball fan if they can name a single scorer. See what I mean?

No, they are doing it for their love of the game and their belief in getting things right. As Duca artfully put it: “We act as curators for the history of the game”.

This idea of being a curator of the game really hit home when I learned that Jim Gates, the official scorer of the Oneonta Outlaws (a member of the Perfect Game Collegiate Baseball League, which gathers college players from across the country to play games in Upstate New York in June and July), is none other than the Library Director at the Hall of Fame – a man responsible for more than 3,000,000 documents related to the National Pastime. In his day job he curates the past, and in his night gig he curates the present.

These men and women, who show up every day and every night have earned a certain amount of respect; and it would be a massive error not to tip your cap to these unheralded stewards of our game.

PLAY BALL!