Fathers & Sons

When I first walked through the gates of Sancet Field (now Stadium) at the University of Arizona, my eyes were immediately drawn to center field. Shagging fly balls out there was the best baseball player I had ever seen. He wasn’t huge (5’11”, 195 pounds), but he was so smooth. He tracked down every line drive, had a cannon attached to his shoulder, and hit the ball a country mile. Little did I know that that guy was the son of former big leaguer Clyde Mashore, who played five years in the National League in the ‘70s, finishing with -1.7 of total bWAR. My new college teammate (however temporarily) was Damon Mashore, who made it to “The Show,” played three seasons, and ended his career in 1998 with a total of .5 bWAR. Advantage: Son.

In Joe Posnanski’s fantastic book, The Soul of Baseball, the late, great Buck O’Neil had the following soliloquy: “Why do you think there are so many fathers and sons in the game? Maybe it’s because baseball is a sport you hand down to your kids. Does a father teach his son how to be a running back? No, see, that’s instinct. Everybody runs with their own style. Does a father teach his son how to play basketball? Maybe, there are a few fathers and sons in basketball, right? But it’s not the same thing. In baseball, you play catch with your son. You teach him how to hold a bat, how to swing it, how to get under a pop-up, how to throw to the right base. You teach him how to run the bases. You teach him how to run back on a ball over his head. You teach him how to throw a curveball. In baseball, you pass along wisdom, like your father did for you in your backyard.”

With apologies to Helen Callaghan, baseball is a sport of fathers and sons. So, in honor of Father’s Day and in keeping with Buck O’Neil’s brilliant insights, let’s take a look at some other apples that have fallen from trees.

Per CBS Sports:

- There are 240 father-son combinations to have reached the big leagues.

- There are 46 active second-generation players.

- Five families have produced third-generation players: the Bells (Gus, Buddy, David, and Mike), the Boones (Ray, Bob, Bret, and Aaron), the Colemans (Joe, Joe Jr., and Casey), the Hairstons (Sammy, Jerry, Johnny, Jerry Jr., and Scott), and the Schofield/Werths (Ducky Schofield, Dick Schofield, and Jayson Werth).

And when Bret Boone’s son, Jake, was taken in last year’s draft by the Washington Nationals, we were given a puncher’s chance of seeing our first fourth-generation player. Suffice it to say, one (but certainly not the only) prerequisite to becoming a Major League player is having a father who did so.

That in itself is not that interesting. What is interesting is that in lineups all across the big leagues you can find the name of a second-generation player who is markedly better than his father. And, when you include two Hall of Famers in the mix, that is high praise indeed. Here is just a handful of these comparisons (all statistics current through June 17th):

Fernando & Fernando, Jr. Tatis: I am not sure we even need to do this analysis. Senior had a fine 11-year career, finishing with 6.4 bWAR. But, if he hadn’t hit two grand slams in a single inning at Dodger Stadium in 1999, we probably wouldn’t know too much about him. Now he is best known for rearing his namesake. Junior is one of (if not the) most exciting players in the game today. He is a five-tool star who does everything better than nearly everyone else. If he can avoid injuries (a valid concern), he is on his way to living up to his $324M contract and possibly to Cooperstown. Sure, that is a long way off; but, in 2.5 seasons he already has 10.1 bWAR, 50% more than dad. Senior may get the biggest piece of chicken, but Junior gets the biggest applause.

Vladimir & Vladimir, Jr. Guerrero: This one is the most fascinating of the father-son combos. Vladdy had a historic career. Over 16 seasons he collected 2590 hits, slugged 449 home runs, knocked in 1496, had an OPS of .931, and ended with 59.5 bWAR. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 2018 with 92.9% of the vote. And yet, Vladito may be better (but not quite yet). The son learned to control the strike zone (“do as I say, not as I do”), hits the ball harder and more consistently than dad, and is off to an incredible start. But at similar places in their careers, dad still outpaces son in nearly all metrics:

| G | H | R | HR | BB | SO | |

| Vlad | 258 | 305 | 154 | 50 | 61 | 137 |

| Jr. | 250 | 266 | 137 | 46 | 107 | 174 |

That said, take a look at this from MLB’s Instagram account:

Dante & Bo Bichette: You will recall that Dante had a great career as part of the Blake Street Bombers in the thin air at Coors Field. He started with the Angels and then moved to Milwaukee before landing in Denver. He rounded out his tenure with Toronto, Cincinnati, and Boston, compiling 274 home runs, an .835 OPS, and 107 OPS+, with 5.6 career bWAR.

Those are fine numbers, and it was a fine career. But if we just look at his and his son Bo’s first chunk of time, we will see how much better the fils is than the père.

| G | H | R | HR | BB | SO | |

| Dante | 178 | 130 | 54 | 18 | 22 | 110 |

| Bo | 142 | 176 | 107 | 30 | 37 | 148 |

Craig & Cavan Biggio: Craig was elected into HOF in 2015. He is clearly one of the best to ever play the game. As such, he left his son, Cavan, with huge shoes to fill. As such, Cavan may be the one kid on this list who doesn’t surpass his father in either skills or (ultimate) stats. Craig came up as a catcher, moved to centerfield, and landed at second base. Cavan is also a bit of Swiss Army knife, playing second, third, and a little outfield, and has actually gotten off to a better start to his career than his dad. But he has a long way – any many hit-by-pitches – to go before he can carry dad’s jock. Considering where they started, it will be interesting to see where they finish:

| G | H | R | HR | BB | SO | |

| Craig | 184 | 140 | 78 | 16 | 56 | 93 |

| Cavan | 205 | 172 | 125 | 30 | 135 | 235 |

One additional note about the above three from Jayson Stark’s “Weird and Wild” column in The Athletic: Last weekend, all three players, all three sons of former big leaguers, hit home runs at Fenway Park two games in a row. That has never happened before.

Clay & Cody Bellinger: Clay Bellinger had an unremarkable four-year career. But, hey, he was a big leaguer. His best contribution may have been passing his DNA to his son Cody. Since Clay only played four years, let’s take a look at Cody’s first four years (which combines the 60-game 2020 and the 16 he has played to date in 2021):

| G | H | R | HR | BB | SO | |

| Clay | 183 | 60 | 57 | 12 | 22 | 82 |

| Cody | 522 | 508 | 337 | 124 | 267 | 466 |

If Cody doesn’t play another MLB game, he has already won a Rookie of the Year, an MVP, and a World Series. It is already clear that Cody > Clay.

Charlie & Ke’Bryan Hayes: This one may be too soon to tell, but we can make an educated guess. Charlie had a very nice career, culminating with his squeezing the last out of the 1996 World Series. Over 14 years, he collected 1379 hits, 144 of which left the yard, and accumulated 10.5 bWAR.

Ke’Bryan is the top prospect in the Pirates organization, may soon be deemed the best defensive third baseman in baseball, and hits like a mule kicks. Putting aside his lack of understanding that you must step on all of the bases when you hit one over the fence, his career looks awfully bright, and it seems he may pass papa in no time flat.

Raúl & Adalberto Mondesi: One might claim this one is too soon to tell, but I think it is safe to say that dad will have bragging rights at Thanksgiving. Raúl played 13 years, hit 271 home runs, and threw runners out with abandon. He finished his career with 29.5 bWAR.

Adalberto is a middle infielder with not much pop (35 dingers over six seasons), not much contact (359 Ks in 1200 plate appearances with 30% K-rate), not much selection (4.2% BB-rate), and a .709 OPS. If you doubled Adalberto’s career and got him to 12 seasons, he would be WAY short of his dad’s ultimate numbers. I guess, theoretically, Adalberto’s 13th season could be Mike Trout-ish and get him the win in the last furlong, but I wouldn’t bet on it.

Bobby & Bobby, Jr. Witt: This one is truly too soon to know, but you know. Putting aside the difficulty in comparing pitchers and hitters, we are stymied by the fact that Junior has yet to reach the majors (despite having an incredible spring training and tantalizing the people in Kansas City). Bobby played with eight teams over 16 seasons, collected 142 wins against 157 losses (if you are into that type of thing), with a 4.83 ERA and a 1.569 WHIP. He ended with 14.6 bWAR. If Bobby, Jr. lives up to even half the hype, he will pass Senior in his third or fourth big league season.

As you may have guessed, there are many more former fathers and current sons we could compare, including the McCullers (Lance & Lance, Jr.), the Pedersons (Stu & Joc), the Brantleys (Mickey & Michael), the Bedrosians (Steve & Cam), the Quantrills (Paul & Cal), and the Shaws (Jeff & Travis). But the players listed above are a great cross-section of the current crop of kids, most of whom are boat-racing the men who taught them the game.

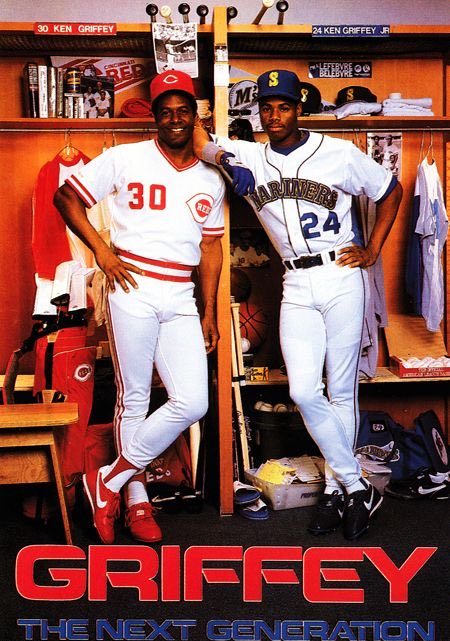

However, regardless of how many records they set or how much money they make, my guess is that they will all live by Ken Griffey, Jr.’s credo: Dad still pays.

Have a wonderful Father’s Day. Grab your pops, or grab your son, or grab them both, and…

PLAY BALL!!