LANGUAGE BARRIER

LANGUAGE BARRIER

Within the past week, two people who I love dearly each told me – separately – that they try to read this blog, but can’t always follow it. That didn’t bother me in the least, because, as I wrote in my very first entry, this ain’t for everyone. I was just happy that they tried. This got me to thinking about why they couldn’t follow. I write short paragraphs, and include pictures, videos, and graphics; so why is it so hard . . . ?

And then it hit me: There is a language barrier; they don’t speak baseball.

Baseball, possibly more than any other sport, has its own language. Sure, football has crazy plays that are nearly impossible to decode/understand (real life sample: “Brown Right Over Flip Zac 73 Chicago F arrow X curl”). And basketball has “pin down screens” and “backdoor cuts” and “alley oops”.

But in describing the day-to-day of the game, listening to it on the radio, or casually having the television on in the background (not Dodger games in 70% of Los Angeles, natch), requires a base level of understanding of what certain oft-used terms mean. So, today I am reaching out to the uninitiated; the common masses who listen but do not hear; who try to understand, but have trouble comprehending.

The next time Vin Scully says any of the following, or Bob Costas starts “talkin’ baseball”, or Pete van Wieren interjects any of the below while being a homer (i.e., an announcer who roots for the team signing his paycheck) for the Braves, you will have a better understanding of what the hell just happened:

A batter hits a soft line drive into left field. What shall we call that? For starters, “line drive” typically means a hard hit ball – a ball hit “on a line”. So, by definition, a “soft line drive” is an oxymoron – let the confusion begin. Listening in the car, you may hear that described as a Texas Leaguer, a duck fart, a broken bat single, or a dying quail. Some refer to it as a flair. In all of the above instances, the batter will be safe at first base.

What about a bouncing ball that makes it into the outfield? Well that could be a seeing-eye single or a twelve hopper or a Baltimore Chop. Again, the batter will have safely made it on base.

And the slow roller that doesn’t even it make it to one of the infielders? A squib or a swinging bunt (another oxymoron). “Slow rollers” don’t normally make it into the outfield – only on special occasions, like Game 6 of the 1986 World Series.

And what to make of the aforementioned line drive? A screamer; laser; pea; seed; rocket; shot. If it leaves the yard then it is a homerun, which might be referred to as a dinger or tater, a dong or a round-tripper. Really hit it hard and it’s a bomb.

Players often refer to homeruns as Jimmy Jacks, which can be shortened to the more simplistic Jack (wherefore art thou, Jimmy?). Whatever you call it, the hitter can touch ‘em all. If hit particularly well, it is a no doubter because that one is not coming back (see, Stanton, Giancarlo). If it barely makes it out, it is a wall scraper or a cheap one:

If the bases happened to be loaded (i.e., runners of first, second, and third base), then that pedestrian homerun becomes a grand slam or a salami.

Sometimes a batter see four balls (as opposed to three strikes), and then he literally receives a base on balls (which, as a call back, is recorded in the scorebook as “BB”). That is also known as a free pass; and when done intentionally – whether at the Little League or another level – it is known as an intentional walk (pretty straightforward), but could also be called four wide ones. Where it gets tricky is when the pitcher doesn’t mean to walk the batter, but doesn’t mean not to walk him. We call that an unintentional intentional walk – again with the oxymorons. Got it?

The flip side is when a batter gets three strikes before anything else good happens. In that instance, he strikes out. Or is down on strikes. Or Ks. If he doesn’t swing at the third strike, he is caught looking and will suffer a ʞ (verbally: “a backwards K”). Old schoolers may say he fanned or whiffed (or, as Dan Patrick might say, “the whiiiiiff!”).

Then there are the pitches themselves. They sound so lame: fastball, curveball, change up. Let’s add a little baseball flair to each of them:

A fastball is a heater. If near the batter’s head, it’s a high/hard one. Some pitchers throw cheese or gas. Whether they throw a four-seamer or a two-seamer, they bring the heat.

How about the curveball? Well, that is an Uncle Charlie (many theories, but actual origins unknown), a bender or, in the case of Clayton Kershaw and pitchers of his ilk, Public Enemy Number One. Some announcers can’t “read” the pitch from their lofty perch above the diamond, so they call everything that isn’t a fastball an off-speed pitch (be leery of any play-by-play guy who uses this term too often). Some call it the hammer or the hook, a yakker or a knee bender. They often come in through the back door, so be wary of a pitcher with a nasty deuce. And pitchers need to get on top of, own, sell, believe in, or bite it, lest it hang in which case the hitter will bang, often resulting in a bomb. Are you still with me?

Curveballs, like clockwork, often go from 12 to 6 or 9 to 3, and sometimes in different directions if the release is 3/4s (i.e., a somewhat sidearm motion) or submarine (i.e., a sidearm motion that borders on being underhanded). To wit:

Hurlers have so many pitches in their repertoire that it is sometimes hard to understand what the announcer says he threw. So, if you hear any of the following, this is what they saw:

- A change-up or off-speed pitch is pitched with the same motion as the fastball, just slower.

- The knuckleball is thrown (?) at a considerably slower speed, with the ultimate goal of taking all spin away from the ball, resulting in the ball acting a like a butterfly as it flutters toward the plate. This pitch has made more big league catchers and hitters look like little league players than anything else in the history of the game.

- A slider is essentially a hard curveball, but with less “break”. It looks like a fastball, moves sorta like a curveball, and makes the hitter more often look like screwball (see, Gibson, Bob or Johnson, Randy).

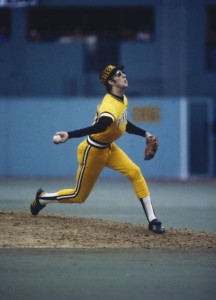

- The screwball is the opposite of a curveball, meaning it breaks in the opposite direction. To get this to happen, a pitcher needs to twist his arm inward on release, such that his palm his facing outward (not a very sustainable motion). While baseball has had many “screwballs” over the years, over the years not too many pitchers could consistently throw screwballs. (Even if you don’t follow baseball, if you lived in Southern California in the early ‘80s, the name Fernando Valenzuela has special meaning. He is the greatest screwball pitcher of all time – a short list, to be sure, but an honor nonetheless).

- Some pitchers load the ball with Vaseline, sunscreen, or good ol’ fashioned spit. Not surprisingly, those pitches are called spitballs. Other pitchers have gotten more creative and used nail files and sandpaper to doctor the ball. If you can control where you scuff the ball, you can make it do all kinds of fun things, and have great success (see, Scott, Mike).

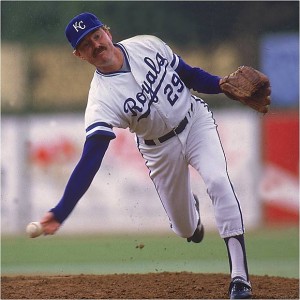

- And, in honor of a special birthday today (answer below if you cannot figure it out), one cannot forget the Eephus Pitch which looks like something you might see at a Sunday softball league. It is essentially lobbed to the plate with an arc of 20-25 feet. The goal is to catch the batter off-guard. (Side note: There is a theory that the term “Eephus” may come from the Hebrew word אפס (pronounced “EFF-ess”), meaning “nothing”.)

Pitchers pitch, and hitters hit, but not all hitters are created equal. Some hitters are mashers who hit seeds and frozen ropes all over the yard. Some studs put on laser shows and others are just plain feared. Some hitters are picky, and will only swing at strikes (see, Boggs, Wade) while others are free-swingers, whose only requirement is that the pitcher actually release the ball (see, Guerrero, Vladimir). Many of the former are said to sit and spit, meaning they sit back and spit on a crappy pitch, refusing to swing. Many of the latter hail from the Dominican Republic, where it is often said, you can’t walk off the island.

On the other end of the spectrum are Punch and Judy hitters. They go up to bat with a wet newspaper and don’t hit the ball very hard. Oftentimes their batting average hovers around the Mendoza Line (which is .200). So, to recap, a hitter sucks and is danger of being released and/or sent off to the Bush Leagues if he only gets 2 hits every 10 at bats; but if he can get 3 hits every 10 at bats, he is a Hall of Famer. Baseball is a difficult and strange game.

Okay. We have dealt with pitchers and their pitches, hitters and their hits. Now we have to deal with the fans. Like kids, they say the darndest things.

You may hear be tough with two and wonder what that means. Well, it means to battle with two strikes, trying not to get fanned. This should not be confused with let’s get two or roll a pair or twist it, all of which refer to the pitcher’s best friend, a double-play (1 pitch turns into 2 outs).

You may hear someone yell to the batter: pick a spot. This doesn’t have anything to do with measles; rather it means a batter should focus on one area, and if the pitch is in that area, they should swing away. A corollary to “pick a spot” is if it’s hangin’ you’re bangin’ which relates to the above-referenced Uncle Charlie. If the pitcher doesn’t get “on top” of the “deuce”, because of the nature of its spin, it may “hang” in the middle of the plate at which point a “stud” more often than not will hit a “seed”, and potentially “touch ‘em all”.

How about inside out. This means to keep your hands inside the baseball (i.e., your hands should stay between your body and the ball as you swing), causing the batter to hit the ball to the opposite field (i.e., right field for righties; left field for lefties).

When a lefty inside-outs a ball, he often hits it in the 5-6 hole which is the small swath of earth between the third baseman and the shortstop. Easier said (and understood) than actually done (unless you are Tony Gwynn). (Note: You never hear about the 3-4 hole.)

We often want the hitter to find a gap. And while some may do this post-game, in this context it means the hitter hits the ball to the left or right of the center fielder, to a place where the corner outfielders (i.e., right fielder and left fielder) cannot reach.

Speaking of corners, when a pitcher hits his corners or a batter takes a pitch on the corner it means that the pitcher is painting the black. Still don’t follow? Home plate is 17” wide, and retreats 8½” towards the catcher, and then meets at a point 12” later. All of the edges are black in color. When you hear any of the above, it means the pitch went through the strike zone above the black part of the plate.

Here is one that you may not hear often, but when you do, you are thoroughly confused: infield fly. Learn this one, and you can impress your friends and neighbors alike. Simply put: runners on at least first and second base and less than two outs, the batter hits a pop fly that can reasonably be caught by an infielder. The umpire immediately calls/signals “infield fly” and the batter is automatically out (regardless of whether or not the fielder actually catches the ball). The runners are then free to run at their peril, and no force play is in effect. Quick and easy. Thank me later.

“Ah, I get it now, but what is a force play” you ask? This can either be easy or complicated. For the casual viewer/listener/reader, let’s make it easy: Is/was the runner forced to go to the next base by the batter or another runner. If yes, the defensive player need only touch the base with the ball under his control, and the runner is “forced out”. If no, the defensive player must tag the runner (while controlling the ball) before the runner reaches the base.

(Editor’s Note: We will cover “tagging up” another time.)

Two more before we go:

When the aforementioned batter is up to bat with runners on first and second or the bases are loaded, it is said that there are ducks on the pond. When that is the case, the batter has a chance to get a steak or a rib eye by knocking the runner in and allowing him/them to score. (Note: When a batter’s hit allows a run to score, the hitter is awarded with a run batted in or an RBI for short; which term has now been bastardized to ribby or rib eye, which eventually led to “steak”. Got it?!?) (Discussion question: Is the plural “RBIs” or “RBI”?)

And lastly, an age old classic. The batter hits short pop fly – normally to the outfield – which is easily caught. That is known as a can of corn. Why, you ask? Because back in the day, grocers used to drop cans of corn (and, ostensibly, other canned food) from the top shelf and catch them in their aprons. Never saw Willie Mays do that!

As with most of these topics, I could write for days. And I am sure many of the readers out there will be quick to tell me about the 10 or 50 other ones I have missed. I look forward to it. But, in the meantime, I believe this is a great primer as we head into the summer. Share this with your loved ones . . .

PLAY BALL!!

Trivia Answer: Dave LaRoche

p.s. Under the rubric of “it takes a village”, I think it is important to note that many friends and readers offer up suggestions for these postings, and I want to make sure I give credit where credit is due. My friend Eva Cohen suggested this topic, and my sister and brother-in-law had confused looks on their faces, so they all should either be thanked or reprimanded.