When Playing Politics, Play to Win

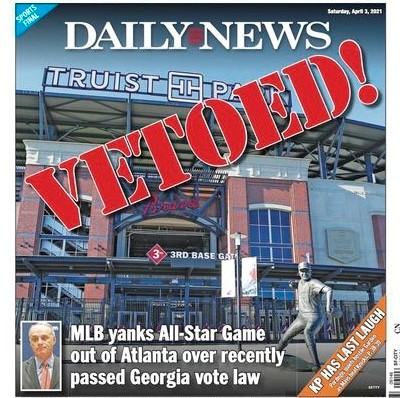

Much has been written, including by my IBWAA colleague Dan Schlossberg, about Rob Manfred’s (unilateral?) decision to move the 2021 All-Star Game from Cobb County, Georgia (it is important to note that the Braves technically do not play in Atlanta) to Denver, Colorado due to Georgia’s new election law. MLB issued a statement saying that this was “the best way to demonstrate our values as a sport.”

More than 200 companies, including Coke, Delta, Apple, and Microsoft have spoken out about the bill and voting rights in general. And, in response, politicians from Marco Rubio to Ted Cruz to Greg Abbott have weighed in, with Mitch McConnell saying that corporations have “the right to participate in the political process [but should] stay out of politics.” Said differently, please keep those sweet corporate donations coming, but please keep your corporate mouths shut.

Our former president jumped into the fray – why wouldn’t he after suggesting that fans boycott football (and a whole host of other companies, products, channels, shows, etc.) – stating, “I would say boycott baseball, why not? I think what they did was a terrible thing.”

In lieu of (or in addition to) a boycott, a handful of congresspersons introduced legislation to strip MLB of its antitrust exemption. We can debate whether or not such an exemption should remain in effect, but what is perfectly clear is that it should not be removed as retribution for a disliked business decision.

These elected officials are doing a lot of pearl clutching about a major sports league wading into the political sphere. These are the same pearls that were clutched when NFL players kneeled for the national anthem, or when WNBA stars wore Raphael Warnock t-shirts, or when the NBA elected not to play after the death of Jacob Blake. But none of these people seemed to have an issue with military flyovers or President Bush throwing out the first pitch in the 2001 World Series, or any of the other countless political events that take place in ballparks and arenas and stadiums each and every year. And, as Howard Bryant rightly pointed out: “For people upset about sports applying political pressure on states, it appears they’ve forgotten the only reason Atlanta even has a baseball team is because in 1965 the city agreed to integrate seating at Fulton County Stadium as a condition for the Milwaukee Braves to move.”

But Manfred’s decision struck a nerve because it went right to the heart of the political process and the means and methods people use the same to get elected. I am not here to opine about the virtues or iniquities of the law, other than to say that the dialogue about it in the media and elsewhere has been misguided, focusing on prior versions of the legislation as well as the wrong aspects of it. The discourse has been exaggerated (at best), and outright wrong (at worst). Those failures – as well as the failures in the law itself – seem to be easily correctable, however.

But claiming sports and politics should not mix is a fool’s errand, a naïve desire, and a willful evasion of the world in which we live. And it is through that lens that I view Manfred’s decision to move the game. I believe that Manfred felt he had no choice. As has been pointed out by Buster Olney and others, if Manfred elected to keep the game in Georgia, this would have been a topic of conversation every day from now until July. Players would have been asked about it, throwing them – oftentimes unwillingly – into a political scrum. This had the potential to splinter clubhouses, forcing players to make what could and would be viewed as a political decision if/when they were given the honor of being an “All-Star.” Some guys just want to play ball.

Further, I am certain Manfred envisioned a scenario in which one or two players elected to forego the game, and then many more followed suit. And, of course, there is the issue of sponsors withdrawing their financial and cultural support for both the game and “the game.” And, as Schlossberg pointed out in his article, Dave Roberts’ ambivalence about managing the NL squad must have had some impact on the Commissioner’s final verdict. If I were sitting in Manfred’s gilded chair, I would fear that I might ultimately be required to cancel the All-Star Game, which would be a blemish considerably harder to erase than letting one end in a tie.

It has been reported that some owners wanted more input. But from my cynical perspective, they less wanted a seat at the table, and more wanted to delay the decision until it was too late, until it was economically and practically unfeasible to actually move the game. And, if for whatever reason, the game was eventually canceled, it would not be the owners’ fault – they would hang the whole mess around Manfred’s neck. They would disclaim any responsibility, and attempt to claim the high ground with their players, sponsors, and communities.

Again, it is easy to see why Manfred did what he did when he did it. But, that resolution seems a bit facile to me.

There is no doubt that this whole situation is fraught. And there is no doubt that politics and race have butted their way into the national pastime in a way that neither fans nor players nor owners nor the Commissioner would have ever wanted. But complaining and being outraged and calling for boycotts are all now competing to become the national pastime. And I firmly believe that some of that could have been avoided by doing the hard thing, by keeping the game in Georgia, and by having a plan.

Had Manfred taken a beat, gathered some very smart, very capable, very experienced, people in a room and given them twenty-four hours to come up with a list of ways to make this work – had he considered it less from a public relations perspective and more a human relations perspective – he may have come to a different conclusion. He may have determined that as much good could come from keeping the game in Georgia as moving it.

If it were me, and I were making $11,000,000 per year to be the leader of a $10B industry and 30 oftentimes self-interested billionaires (actually only 23 billionaires, and 7 hundred millionaires, but let’s not quibble) of various political leanings, I would have come up with a different solution.

To start, I would have gathered Stacey Abrams, Curtis Granderson, and Hank Aaron’s family to issue a statement denouncing – with specificity – the new Georgia voting law. I wouldn’t have relied on Democratic talking points or an early version of the bill. I would have quoted non-partisan election experts to explain – in clear and simple language – how and why this new law is intended to and will disenfranchise people of color.

Next, I would have laid out a comprehensive plan of how MLB intends to use All-Star week to highlight the inequities of voting laws, not just in Georgia, but across the country. This would include setting up voter registration events in Atlanta, at Truist Park, and at every MLB stadium each day of the All-Star break (utilizing the same infrastructure that made NBA arenas voting locations, and MLB parks Covid testing/vaccination sites).

And then I would re-affirm MLB’s plans to honor the late, great Henry Aaron at this year’s game. But, I would make it perfectly clear that MLB is going to focus on all of Hank’s on-field achievements as well as his civil rights advocacy. And, if they were willing to do so, I would ask Hank’s family to come on the field before the game and read a statement about his activism and how Hank would view the current state of race relations and civil rights in this country.

Lastly, I would use my power as the Commissioner of Baseball to pressure each team to make hefty donations to organizations dedicated to advocating for stronger and more equitable voting rights. And then I would commit MLB to match those donations. Utilizing my bully pulpit at the annual State of the State press conference, I would further explain how and why keeping the game in Georgia, and all of the social justice events around the event, have been a net positive; and how MLB strives to be and continues to be a leader in making positive change in communities across the country.

From my perspective, doing those thing would actually “demonstrate our values as a sport.”

But hey, that’s just me.

On Opening Day Manfred told ESPN he wasn’t moving the game. By the next day, he said he was. What happened in-between is anyone’s guess. But based on what Stacey Abrams, Jon Ossoff, and Raphael Warnock had to say about the decision, I feel confident that none of them were included in the deliberations. Manfred played politics, but he didn’t play to win. And, as a result, businesses and workers and fans in Fulton and Cobb counties, and the civic engagement of the country, all lost.

PLAY BALL!!